The Golf Artist

Robert Trent Jones Jr. can't tell you how many miles he's traveled, though 10 million might be the starting point. He can't tell you how many hotel rooms he stayed in, though it wouldn't be a reach to guess it's close to 5,000. He can't tell you how many hands he's shaken, though he's likely to have squeezed at least 100,000 palms. There are two figures that he is certain of—270 and six.

That would be the number of golf courses he has designed and the number of continents those courses span. In a career of more than 50 years, Robert Trent Jones Jr., 76 and still going strong, has amassed a global portfolio that would doubtless please his late, great father, for it was Robert Trent Jones Sr. who established golf course architecture as a professional and marketable undertaking and took his services across the continent—then around the world—for the second half of the 20th Century.

With a built-in nameplate, Trent Jones Jr. followed in those grand footsteps, traveling to all corners of the earth to move dirt around and create iconic golf landscapes. From the National Golf Club in Australia to the Le Meridien Moscow Country Club in Russia to Bro Hof Slott Golf Club in Sweden to Port Edward in South Africa to Margarita Island in Venezuela, Jones has brought together his considerable talent and boundless ion to render some of the most well-regarded courses on the planet.

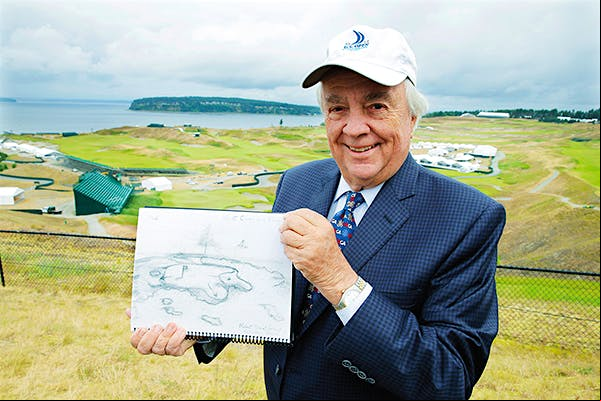

But this past summer, on the spectacular coast of the modest port city of Tacoma, Washington, a Robert Trent Jones Jr. golf course thrust him into the international spotlight and illuminated a career that by any measure has been filled with accomplishment and satisfaction, not to mention intrigue and occasional danger.

Chambers Bay Golf Course was the site of the U.S. Open, our national championship, and what a championship it was with Jordan Spieth, the hottest player in the world, winning in memorable fashion. This was the first U.S. Open contested on what is close to pure links, one entirely invented by Jones and his team. The unpredictable nature of the rolling, sandy, hummocky terrain tests a player's psyche as much as his talent, and there is a single tree on the course proper, merely a wall-hanging in back of the par 3 15th green.

As Jones sat in his home in Woodside, California, this spring, talking expansively and often rhapsodically about his long career, he would make one thing clear about Chambers Bay: "It is everything I know about the game of golf."

Everything he knows about golf and golf course design was gathered first from his prolific father. Robert Trent Jones Sr. built his business across the United States, into the Caribbean, then into Europe, Africa, South America and Asia, a reach that exceeded any designer who had come before him. In doing so Jones Sr., who insightfully realized that he could actually market his talents, firmly established the word "architect" as a major component of the game.

"Golf course architects weren't really well known [at the time]," says Jones Jr. "They were like set designers. It may have been a fabulous set, but people cared more about the performers and the play. I think that changed when people like [Alister] MacKenzie and [A.W.] Tillinghast and even [Donald] Ross, architects from the British Isles, really had a point of view and worked to achieve it. But it really changed with my father. He popularized the idea that yes, there is an architect. He'd know something about the game. He didn't have to be a professional, but he had to be creative. And he had specific knowledge about agronomy, drainage, all the climate things involved in growing grass."

All of these elements of golf have come together for Robert Trent Jones Jr. at Chambers Bay. In a competition with more than 50 other architects, Jones' firm won out by presenting officials of Pierce County, principally then-county executive John Ladenburg, with a proposal that exceeded their original expectations: Jones would design a course that could host a major championship.

On the site of a degraded sand mine, a site that had been used for many industrial purposes, a site that needed substantial remediation before a single blade of fescue grass could be grown, Jones and his team—his partner Bruce Charlton, on-site architect Jay Blasi and shaper Ed Taano, fashioned a links-style course with the aesthetically empowering backdrop of Puget Sound and the surrounding hills and mountains, and the ever-so-links-appropriate rail line running between the bay and the course. And once the project was moving along, United States Golf Association executive director Mike Davis became part of the equation.

"[At Chambers Bay] we told them they had the opportunity that very rarely you could do: a championship golf course near the sea that might be worthy of hosting a national championship," says Jones. "We didn't say U.S. Open—well, eventually we did. The brief to the 55 architects who responded was 27 holes as part of the effluent plant's use of reclaimed water. We gave them that, then said how about 18 great holes and space for galleries to watch?"

The course and the championship had its share of controversy, but what U.S. Open doesn't? The browned out fescue fairways and the greens mottled with poa annua grass had some players complaining bitterly. But those in contention, Spieth, Dustin Johnson and Rory McIlroy found Chambers Bay exhilarating and the end result thrilled Jones.

"I think the leaderboard speaks for itself. The leaderboard validated the course and the course validated the leaderboard. End of story," says Jones. "And the back nine on Sunday was everything anybody could want. The course took it from you with double bogeys and gave it back to you with eagle putts. What else do you want? That's the best you can have in championship golf.

"From my perspective, it was an enormous success. Think of it this way: When Beethoven's Ninth Symphony first played in Vienna, it got mixed reviews because the music was different. They are still playing that symphony 200 years later. This golf course is not going away. It's a major work. It's an ode to golf joy. It's exactly as I as an artist wanted."

Chambers Bays has some of its roots in old-world golf, from Jones' experiences playing the game in Scotland and Ireland and England. It also has elements of his first attempt at links-style golf, at Spanish Bay on the Monterey Peninsula of California, a collaborative effort with golf great Tom Watson and long-time golf official Sandy Tatum. Jones would then go on to design links-style courses in Australia at the National Golf Club, and in New York at Long Island National, near the very roots of the American game at Shinnecock Hills and the National Golf Links of America.

The core of Jones' work at Chambers Bay remains the same as all the courses he's designed around the world: to work with the land that is given, to be true to the environment, to enhance the most aesthetically pleasing elements and provide a course of varying challenges.

"For me personally, what characterizes my work—and it's impossible for me to be my own critic—I like a reasonable challenge, I like it to appeal, to make you want to play again," says Jones. "That it is a course that will yield, but only to good thinking and good shot making. Golf is a game of failed perfectionists. You always think you could do better."

For the past 15 years, Jones says he has been focused on what he calls golf art. "I understand the craftsmanship of it, I understand the aesthetics of it that is appealing and attractive to even the non-golfer. If you are to say what is a beautiful garden, the Wisley Gardens outside London or the Butchart Gardens in Vancouver, there is something about such gardens that when you walk into them you want to be there and is so beautiful in any direction you look."

For Jones, golf is in part a garden, and the great courses are great gardens.

"So San Francisco Golf Club is one of them, Pine Valley is one of them, Cypress Point is one of them, Pebble Beach is one of them. As in Cypress Point, the setting is principally the reason, but the bunkering is artistically crafted. San Francisco is completely crafted being an inland, suburban setting. Tillinghast did that bunkering and I say to myself, how did he do that? It's so good. So there is a form of aesthetics that is manmade, both to a golfer's eye—which is different from the aesthetic eye—but they sometimes go together. To make it a beautiful experience, that is where I've been going."

He trusts that the beautiful experience has been captured at Chambers Bay, a course he describes as a three-dimensional links, with its 200 feet of elevational change. The challenge is the equal of the beauty.

The challenge of Chambers Bay starts at the tees, which aren't quite conventional, twisting and turning in a sort of ribbon effect and also unusually undulating, not flat.

"At Chambers Bay there are no trees and no water hazards, so how are we going to defend?" says Jones. "I said it starts on the tee. A tee is the letter T, but it goes back to ancient Egyptians saying ‘begin here.' Start the pyramid here, start the building of the Sphinx here. It's a surveyor's mark. For us, the tee is flat. Why not make it irregular, a continuation of the fairway, but moving. [Mike Davis] says that's pretty radical. I say no, it's what we have at the short course at Pine Valley. You just drop the ball and play.

"Now you are asking the best players in the world to think, and thinking has always been the hallmark of our strategic design. You'll be between the markers, but it might be higher over there and lower over here. You'll have to think about your stance. You might have to hit a ball that's like landing on an aircraft carrier at sea in high waves. We are combining the unpredictability of the stance with the unpredictability of the terrain to think about a shot."

The thinking part of golf has always been important to Jones, though no more so than the thinking part of life. He's a graduate of Yale and attended Stanford Law School, which is what established this New Jersey boy in the west. He found the law too restraining, and decided to go to work for his father. His younger brother Rees, who also attended Yale then went on to Harvard, responded early to his DNA and became an architect of considerable achievement and earned the nickname "Open Doctor" for his work with the USGA in reinventing U.S. Open courses.

As Jones Jr. expanded his own opportunities (there was his father's name to draw on) he also expanded his intellectual horizons. He became a member of the California Parks & Recreation Commission and was elected its chairman in 1982. When he had some political aspirations, he was appointed to the Helsinki Accords delegation, along with his wife Claiborne, in 1980 during the Carter istration. He was a board member and president of Refugees International. He met presidents and prime ministers and kings and was an acquaintance of Maria Corazon Aquino, the woman who eventually became president of the Philippines after leading the charge to oust dictator Ferdinand Marcos.

With such a résumé, one could wonder how golf has enriched Jones' life. But it opened doors to him that were otherwise closed. He was drafted and wanted to fly, wanted to be a pilot, but was rejected due to his vision (it was 20-25) and a bleeding ulcer.

"What did golf do for me? I got to see the world," he says. "But not only that, I got to participate, literally hands-on, in cultures I had never experienced. I didn't speak the languages, other than Spanish. I did 25 golf courses in Japan. You have to find a way to work in their culture and learn from them. You have to be engaged. The gift that the game gave to me was to have extraordinary experiences at many levels of other people's societies.

"In my public life, not my professional life, I devoted myself to certain causes. Whenever I saw extreme poverty or oppression, I ed certain groups that fought to alleviate that, for example Refugees International. Claiborne was a member and I was a member of the Helsinki Accords delegation, appointed by President Carter in 1980. She worked on human rights. I applied some of the experiences I had working in some pretty tough places, the Soviet Union, China and even tougher places like Indonesia where there was the Year of Living Dangerously with blood in the streets."

He developed a certain patience and perseverance. His Meridien Country Club outside of Moscow took 20 years from the germ of the idea until the course finally bloomed in 1994. Jones had accompanied his father on a trip to Russia along with Dr. Armand Hammer, the oil baron and industrialist who sought peace and closer relations between the United States and Russia and who felt golf would provide a meeting place for businessmen and leaders of both countries. The negotiations started during the regime of Leonid Brezhnev and the project finally got underway during Mikhail Gorbachev's rule. The deal was announced during a summit between Gorbachev and President Ronald Reagan in 1988. "I was in a back room talking about golf balls with of the Supreme Soviet," says Jones.

Getting the chance to bring golf to Russia and other parts of the world was part and parcel of his view of the sport. "Sport is the way to resolve the human-nature of conflict," he says. "It's not always going to work out, but at least you are not killing each other. I'm probably an existentialist. I don't know what this is all about, all I know is that I'm here and I'd love to make it heaven on earth, rather than hell on earth."

During what little down time he's had during a very full career, Jones has expressed his thoughts through poetry, writing about golf and his life's experiences. Among those poems, which he produced in a bound volume for friends and acquaintances this year called Rhyme & Reason, are an ode to his late father, who died in 2000, and a testimony to the World War I battle experiences of the legendary Tommy Armour, from whom Jones took lessons at Winged Foot.

Warner "Butch" Berry is a San Francisco criminal attorney and fellow member of the San Francisco Golf Club who has often been Jones' ear and counsel. He has been a sounding board for Jones' polyglot of opinions and his need to recite poetry.

"There are people who think he's egotistical and all that. I just think they are misinformed," says Berry. "They see him once, listen to him once, they base their opinion on a hit-and-run exposure. When his dad died in 2000, Bob and I got to really know each other and became very close. He's godfather to our little one. His wife and mine are very good friends. We are sort of his bailout option. He can come to our house and drink wine and eat food and recite his poetry. He's just good company. We love the guy.

"He's sure of his opinions. He does not hide his light under a bushel, that's for sure. He's confident of his assessment of an event, a person, a situation, an assignment, a job. But he's not egotistical because he talks about things. A lot of the egotistical ones don't give you much of themselves. Bobby likes the intercourse of conversation and debate. He has multiple interests. He loves literature, he reads a lot, he thinks. I don't know when the guy sleeps. He's always doing something, whether it's drawing a golf hole or writing a poem or writing a letter."

And his poetry?

"Terrible," says Berry. "I think it is. He doesn't. So we engage, he reads it, we laugh. He isn't trying to publish anything. He doesn't think he's Robert Frost. He's more Jack Frost than Robert Frost."

The poet in him has come across to Pete Martland, the CEO of Sentry World Insurance, the company for whom Jones designed the first destination course in Wisconsin in the 1980s. Jones was called back to re-invent the course under Martland's watch.

"There was no doubt in our mind that not only was he renowned as a course architect, but the idea of someone redoing a golf course 30 some years after he first did it, that had a lot of appeal," says Martland. "Bob is also a great communicator, and he can explain concepts very well to the lay audience, which I would include myself, that makes him a compelling person to want to work with. Never any doubt we would work with Bob."

When the work was done, Martland was not only pleased, but charmed. "When Bob talks about golf and golf courses he talks very poetically. In fact, he is a poet," says Martland.

"He pulls you in to the romance of the course and he talked about the stories behind the creation of the first course. He told it with humor and poignancy. He made the course come alive in ways that were very compelling. His artistry—he talks in artistic or poetic about a golf course, not in technical . Although the technician, the engineer in him, comes out when you are on the course and he is talking about the details and the decisions about holes."

The players in the U.S. Open had to make a number of decisions they may never have made before about how to play Chambers Bay, which was designed by Jones so that several holes can be played entirely differently each day.

"This is the first golf course since 1970 that we've gone to that's really a new golf course and the architect who conceived of it is still alive," says the USGA's Davis, the man who was responsible for the course's setup during the Open. "Ironically, it was Bob's father Trent Jones Sr. who was the architect back in 1970 at [new U.S. Open site] Hazeltine. Then you have Rees Jones, who has been so engaged with U.S. Opens and the architecture over the years. So you talk about a family that has influence over the U.S. Open Championship, it's just amazing."

And Robert Trent Jones Jr. will continue to have influence over a national championship in 2016 when the USGA brings the Women's Open to CordeValle, a resort and club south of San Jose, California. CordeValle is nearly the polar opposite of Chambers Bay, a traditional layout set among the golden hills of California.

"CordeValle is old California," says Jones. "You come into the valley of golden glorious hills. There was no housing included in the project, simply a lodge, a spa and golf course to preserve the glorious valley. It is a golf course that is challenging to men and women and many championships professional and amateur have been played upon it.

"It's a golfer's golf course. The greens are relatively close to the next tee. It's at the low-lying part of the valley. Because there's no housing, you don't cross any roads. You move from hole to hole seamlessly, and that's what I call core golf or pure golf."

As Jones describes his efforts at Chambers Bay before the Open last summer, his literary style comes through as dramatically as his architectural style. "I think this course at medal play will be relentless," he says. "You are going to have think about every shot all the way through. Add to that the setup. If I'm the composer and Mike Davis is the conductor and the players are the symphony, it's going to be extraordinary music."

It's the poet in him, and in everything he does.

Jeff Williams is a contributing editor of Cigar Aficionado.